Dersim

Munzur Vadisi The Newyork Times’ta

The Newyork Times muhabiri Dersim ve Munzur Vadisi’nin güzelliklerini yazdı.

Dersimnews.com – Dünyanın en popüler gazetelerinden biri olan ABD’nin The Newyork Times Gazetesi, Dersim ve Munzur Vadisi’ni sayfalarına taşıdı.

The NYTimes muhabiri Dersim gezisini anlattığı yazısı::

Finding Paradise in Turkey’s Munzur Valley

Deep in the rugged heart of eastern Anatolia, the resilient Alevi Kurds open their hearts and homes to a visitor.

Deep in the rugged heart of eastern Anatolia, the Munzur River flows from the base of a skyscraping limestone massif, wending its way into the world across a grassy valley cradled between dog-toothed peaks and forested hills. The water is impossibly clear and numbingly cold and, to most of those who visit its source, sacred. “It’s easy to feel close to God here,” I was told by one follower of the mystical Alevi religion, who, like hundreds of other women, men and children, had come to the springs — called Munzur Gozeleri — on a scorching July afternoon.

They had come to pray and light candles in the nooks of boulders, and to immerse themselves in the bracing waters. They had come to sacrifice sheep and goats on a hill above the river, blessing new marriages, honoring dead relatives, hoping to help heal sick children. And they had come to eat: Each family that brought an animal to slaughter took its freshly butchered meat down to the riverside, where it was roasted or stewed over an open fire, served under shade trees with flatbreads, cheeses, olives and tea, and shared with friends and strangers alike. The scene was informal and festive, like a community picnic, striking an easy balance between the spiritual and the recreational.

I had gone to the river’s source in July 2014, to meet with a local Alevi leader, called a dede, to learn about the religion: a gnostic amalgam of Islam, Zoroastrianism, shamanism and other influences, which emphasizes inner spiritual growth over outward displays of faith, and regards nature as holy. The vast majority of people in the region of Dersim, through which the Munzur River flows, are adherents of Alevism, and are also ethnic Kurds (though many Alevis in other parts of Turkey are ethnic Turks).

Hasan Hayri Sanli, known as the Hayri Dede, whom I met at the springs, has written five books about Alevism, and was happy to talk with a rare foreign visitor. He was nearly bald; his mustache was a thick brush of white and silver bristles; his hearing aid worked intermittently. His voice was rich and emotive, so I grasped the feeling behind his words even before they were translated for me by a young woman from the nearby town of Ovacik, who was studying to be an English teacher.

Among the many things the dede said during our wide-ranging conversation, one leapt out: “We don’t believe there’s a paradise waiting for us after we die. For us, heaven and hell are here on earth.”

Though he meant it as an explanation of an essential Alevi belief, it was also an apt description of the Munzur Valley itself — where the landscape is awe-inspiring, people are phenomenally friendly, and great suffering and injustice have been endured. At the time of my conversation with the Hayri Dede, the threat of a major hydroelectric project, which would dam the Munzur River in several places and destroy much of the valley, loomed over the area.

I first visited Munzur in 2005. I was traveling through eastern Turkey, planning my route with topographical maps, and one land form leapt off the paper and into my imagination: an oval-shaped basin sitting about 5,000 feet above sea level, ringed by mountains. It was far from major cities and tourist destinations — exactly the kind of place I wanted to go.

I aimed for Ovacik, the largest town in the upper Munzur Valley, now with a population of 3,700, and spent a few days wandering out to the small villages beneath the soaring Munzur Mountains. Wherever I went, I was welcomed into stone-and-mud homes to share tea and food with the Kurdish shepherds who lived there.

With endless hospitality and the sense that I’d found a little-known geographical gem, I felt as if I had stumbled into an Anatolian Shangri-La, which was tarnished only by the imposing presence of Turkish military and police.

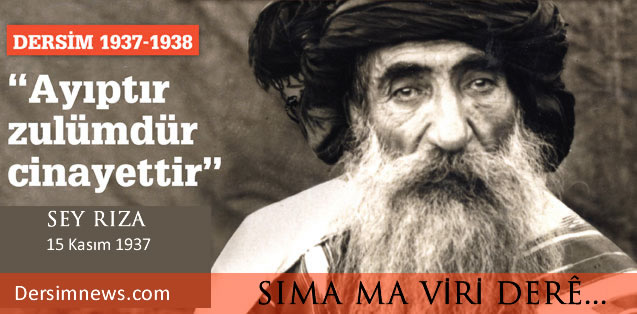

Since before the founding of the Turkish Republic in 1923, the Dersim region, most of which is officially part of Tunceli Province, has been known for its independent streak. In the mid-1930s, when the Turkish state began efforts to dilute the region’s Kurdish identity, tribes in Dersim resisted. Government forces responded with the Dersim Massacre of 1937-38, killing between 14,000 and 80,000 people. Thousands more were forcibly displaced to western Turkey.

Decades later, in the early 1990s, the hills, mountains and canyons of Dersim were infiltrated by the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party), an armed rebel group fighting for greater autonomy for Turkey’s Kurds. Despite local ambivalence toward the PKK, the Turkish military began a scorched-earth campaign against the guerrillas in and around the Munzur Valley in 1994.

During what’s known as “the Evacuation,” more than 100 rural villages in Tunceli Province, where Kurdish Alevi families had lived for hundreds of years, were destroyed; the fields, orchards and forests around them were burned; many men were jailed on suspicion of aiding the insurgents. These tactics largely punished innocent civilians, searing them with a sense of bitterness and mistrust toward the government.

On my first visit, the PKK was apparently still operating in the area. Turkish army vehicles cruised the few streets of Ovacik, and a fortified military commando base loomed on the edge of town. I was stopped daily by uniformed men who examined my passport, unhappy that a foreigner had strayed into their jurisdiction. When I tried to hike into the mountains, I was chased down and forced to turn back by two officers who blocked my way, pointing to the highlands and shouting “Terroreests! Terroreests!”

Locals in Ovacik scoffed at the idea that I would have had any trouble with militants but, they said, it was too cold then, in November, to explore the mountains; I should come back in summer, when families moved their herds up to the alpine meadows and stayed there for months. I promised myself that, one day, I would.

In many ways, since so few people there spoke English, I didn’t realize where I had been until after I had left. I’d had no idea that I was in one of the most biodiverse regions in eastern Anatolia, where bear, wolves, lynx and ibex roam the hills and where thousands of plant species grow. Much of the landscape that so enchanted me, it turned out, was part of Munzur Valley National Park, one of Turkey’s largest protected natural areas, created in 1971.

And it was only later that I learned that Munzur is considered by many to be the heartland of the Alevi religion, where holy places, all of which are natural features of the landscape, are found in abundance, and where the region’s isolation has insulated it from the influence of Sunni Islam, helping to keep its unique Alevi character relatively pure.

To my shock, while researching Munzur, I also discovered that much of the valley was slated to be drowned behind a series of dams. According to Turkish newspaper articles, as well as an in-depth report, “The Cultural and Environmental Impact of Large Dams in Southeast Turkey,” by Maggie Ronayne, an archaeologist at the National University of Ireland, Galway, many sacred places would be submerged. The villages that survived 1994 would be evacuated, and huge tracts of wildlife habitat would be flooded, even within the supposedly protected national park.

The worst of the impact on the valley had been delayed by passionate protests and legal challenges, but from reports I’d seen, it appeared that the Turkish government wanted to press forward with the hydroelectric projects and was not giving up.

After years of putting it off, I finally made it back to Munzur last July. This time, in case it one day slipped beneath the rising waters of a chain of reservoirs, I planned to begin documenting the daily life and Alevi traditions of the valley, so I asked a friend and filmmaker, Cat Cannon, to join me.

We headed for Ovacik, which is far more scenic, slower-paced and 30 miles closer to the river’s source than the valley’s largest city, Tunceli. Even before arriving, I noticed a huge difference from my previous visit: There were no military checkpoints anywhere along the road. In Ovacik, the military base had been dismantled, and the police never asked to inspect our passports. Cat and I were free to go anywhere we wanted. The truce made in March 2013 between the Turkish government and the PKK was holding well enough.

Ovacik’s center is two blocks long by three blocks wide and is small enough that, after a few days, almost every face greets you with a smile of happy recognition. Shops display their wares along the sidewalks; you can buy pitchfork tines, scythe blades and wood-fueled water heaters as easily as fruits and vegetables. Men, and sometimes women, sit beneath teahouse awnings, playing cards or Okey (Turkish rummy).

There are two banks, three Internet cafes, four shoe stores and a couple of bakeries that vie for the title of “town’s best baklava.” With little traffic, people often stroll in the streets, and one rarely loses sight of the mountains that rise behind the town, or the fields along the flood plain in front of it.

Though there are a few hotels and restaurants, there’s little in the way of recreational infrastructure in Ovacik: No companies offer guided trips around the valley, and there is no tourist office or marked trail system for Munzur Valley National Park.

As it turned out, we didn’t need any of those things. Less than a minute after we arrived by minibus, we met Serde Yerlikaya, who was home on summer break from university in Ankara and was fluent in English. She agreed on the spot to help translate for us during our stay (for which we insisted on paying her) and we became fast friends. When weddings were held, we would go along with her and her older sister, Bahar, who taught us local dances and swept us into the circles of revelers.

Most days, Cat, Serde and I ventured away from Ovacik, walking, hitchhiking or taking taxis to villages around the valley, where beautiful old stone houses sat beside new ones built of concrete. We sat on porches or in gardens, listening to musicians sing dirges while strumming seven-stringed baglamas. We watched women bake bread by rolling and stretching dough into pizzalike circles, which they draped over curved pans that sat atop small fires. We drank countless glasses of tea and fresh ayran (yogurt, water and salt), and were fed homemade cheeses, roasted peppers and honey straight from the hive.

We also visited sacred Alevi sites, called ziyarets. Some are seemingly random boulders topped with piles of pebbles, or trees to which strips of cloth had been tied — each pebble, each piece of cloth, is a prayer left behind by an Alevi. Other ziyarets are major land features and pilgrimage sites where miracles are said to have occurred.

According to legend, the springs at Munzur Gozeleri gush from the ground where a saintlike figure named Munzur accidentally spilled milk from a pail. On a towering ridge with vistas of the valley, a man named Belhasan is buried where he once gathered snow to show to his brother in a faraway city — and the snow never melted.

At Duzgun Baba (just outside the Munzur Valley), a mountainside cave became the home-in-exile of a shepherd who could turn bare trees green with a touch of his stick; if you can spoon water out of a hole in the back of the cave, you are a pure soul (I passed the test). A nearby pile of stones about as long as a city bus, and half as high, marks Duzgun’s grave. The faithful remove their shoes and walk around it three times, perhaps leaving photos of loved ones, lighting candles or adding stones to it.

Though there is one mosque in Ovacik, locals apparently never go to it. “It was built only for the police, who aren’t from here,” I was told. In fact, though they sometimes refer to God as Allah and revere the prophet Mohammed and especially Ali, Shia Islam’s first imam, people I met insisted, “We are not Muslim.” Their religion, they said, had Zoroastrian roots, and their ancestors had adopted some trappings of Islam only so they wouldn’t be massacred by Muslim armies many centuries ago.

Alevism and Islam seemed to share little in practice: No one I met fasted for Ramadan or read the Quran. Women dressed however they pleased, those younger than 40 often wearing tank tops (at least in July, when daytime temperatures hover around 100).

Alevi men and women worship together, preach tolerance for all religions and don’t seek converts. They reject Sharia law as rigid and overly focused on external displays of piety, while they value instead an inner spiritual development, which is mainly practiced by treating people with kindness and generosity, rather than through ritual.

This is not just a nice idea that the people in Munzur agree with in theory, then ignore; it is a fundamental element of the culture that flows effortlessly from the people, and makes traveling there an absolute joy.

For our more ambitious endeavors, Cat and I relied on Akin Gedik, the helpful manager of the Doga Turistik Otel, a modern hotel with a popular restaurant, in Ovacik. When we told him we wanted to explore the mountains, he found people willing to accompany us: a local man, to show us the way, and a multilingual German anthropologist who had been in the area for several months, to translate.

We spent five days on a route that looped through the burly core of the Munzur Range, where meadows — more rock than grass — unrolled beneath a serrated skyline. We camped near the white cone-shaped tents of the families who summered there, grazing their animals and making tulum peynir, a cheese that is produced in the chilly alpine air, then transported on horseback to town, where it sells for $8 a pound.

Watching women milk their flocks, veiled in twilight, protected by huge (and surprisingly affectionate) guard dogs, it might have been easy to romanticize this idyllic pastoral existence. Any such fantasies, however, were quickly dispelled by the shepherds, most of whom said that the joys of mountain living were outweighed by its inconveniences, like the lack of electricity and mobile phone service. Those in their teens and 20s, who migrated with their parents, expressed little interest in continuing their seasonally nomadic way of life.

With the fate of Munzur on my mind, I asked Akin, the hotel manager, about the multi-dam hydro project that was to be built by Turkish, American and European contractors. Akin suggested we visit the first dam that had been built within the national park, on the Mercan River, a tributary of the Munzur.

At the bottom of a gorge, where a sheer canyon opens into a steeply terraced valley, the free-flowing white-water of the Mercan pours into a turquoise pool, blocked by a concrete wall. While this dam is too small to flood any villages, the trickle of water that flows downstream below it is too meager to support native fish populations.

After the dam was completed in 2003, local opposition to the rest of the project erupted. Aside from outrage at the prospect of losing their homes and their livestock-based livelihoods, the Alevis of Munzur objected to the threats to the natural world, which they view as sacred. Damming the river “is the same as harming our body,” Baris Yildirim, an activist lawyer, told me.

Email requests to several Turkish officials for information about the dams went unanswered, but in the past, the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources has said that its intention was to promote development by providing more electricity to the region. Locals, however, didn’t believe it. Many are convinced that the primary purpose of damming the river is to evict them from the area once and for all. Why? “Because we are Kurds and we are Alevis,” Mr. Yildirim said. “They want us to leave and forget who we are.”

On Oct. 31, 2014, anti-dam activists won what the Hurriyet Daily News called a “landmark victory” in court, halting construction, at least for now. If the dam plans are resurrected, as they may well be, the people of Munzur will undoubtedly rise against them once more. “We will win,” I was told, “because we will never stop fighting for this place.”

It was easy to understand their ardor, even without sharing their unique spiritual relationship to Munzur. Many times, when nothing remarkable was going on, I was struck by moments of pure bliss. Just walking between villages at dusk — with the high peaks shrouded in smoky violet, shepherds ambling through the fields with their flocks, bells a-jingle, and the first stars sparkling in the sky over a dark and ragged horizon — was as extraordinary as it was mundane. It was obvious that the essence of this generous and open-minded culture was somehow infused with, and perfectly attuned to, the essence of the place. They seemed inseparable.

The day I spoke with the Hayri Dede at the source of the Munzur, he ended our conversation by reciting a poem he had written. Near the end, his eyes filled with tears. Serde translated the last two lines: “When I die, burn my body and scatter me over Munzur.” It was a love poem to the valley.

His heaven, clearly, is here on earth.